Behind the headlines: bird fatalities and wind turbines

Posted on 12 Apr 2013 in Commentary

Once again, it’s been a busy couple of weeks in the national headlines for wind farms, with both the Daily Mail and The Telegraph putting the spotlight on the impacts of turbines on rare birds. In a recent article, the Mail cited figures from the Spanish Ornithological Society and Birdlife, claiming that “110 -330 birds a year are killed by each turbine”, a figure broadly extrapolated in the article to suggest that “…this means that worldwide, wind turbines kill at least 22 million birds a year” – rather a large figure by any means and worthy of further exploration.

Protecting bird numbers and ensuring the protection of rare species remains key. Bird life not only contributes to overall biodiversity, but also provides numerous economic, cultural and environmental benefits.

Yet a closer look behind the headlines shows on balance that the detrimental impacts of wind farms on bird mortality rates – whilst of course undesirable – are, overall, relatively low. Both sides of the debate can use individual wind farm case studies and accompanying fatality figures without the underlying contextual detail or cross-comparisons, to put forward arguments for or against wind developments.

In reality, the threat posed to bird species by climate change is arguably far greater than the threat posed by wind farms and turbines. Given the need to cut greenhouse gas emissions to help tackle climate change, rolling-out low-carbon technologies, including wind developments as part of that energy mix, remains a critical part of the UK’s action plan to cut its greenhouse gas emissions.

In this article, we draw on peer-reviewed research to take a more detailed look at the issue of bird fatalities and wind turbines, to provide the broader context behind the headlines.

Bird fatalities and wind turbines: the evidence

Typically, bird fatalities caused from wind developments are linked to direct turbine collisions, loss of feeding or nesting grounds, or disruption to migration routes or flight paths (Lucas et al, 2007). Generally, when appropriately sited and compared to other causes of death, the number of bird fatalities linked to wind turbines is relatively low. In their latest wind farm policy statement, the RSPB note “if wind farms are located away from major migration routes and important feeding, breeding and roosting areas of those bird species known or suspected to be at risk, it is likely that they will have minimal impacts” – a view supported by the Institute’s latest policy brief on onshore wind. Whilst any bird fatalities are clearly an undesirable consequence of wind developments, the death rates associated with turbine collisions are still orders of magnitude lower than other human causes of bird deaths – such as domestic cats or traffic – as illustrated below.

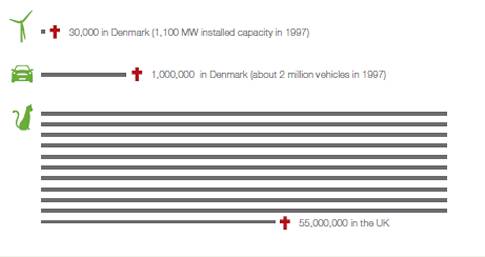

By way of example, annual bird deaths in Denmark caused by wind turbines and cars, and annual bird deaths in Britain caused by cats:

Source: Based on McKay, 2008 – in the latest GRI Policy Brief

The RSPB suggests that “poorly sited wind farms can have negative effects on birds, leading to potential conflict where proposals coincide with areas of high activity for species of conservation concern”. Wind farms in California and Spain act as documented cases-in-point where poor siting decisions can increase bird fatality rates – particularly where migration paths or areas with high bird population density are not considered. Ultimately, “collision rates can be much higher in poorly sited wind farms”. Selecting sites away from important breeding colonies can also help to reduce bird mortality rates.

A study published in April last year in the Journal of Applied Ecology found minimal impact on birds from direct collisions with operating turbines and suggested, for the sites studied, that impacts on bird populations were typically larger during the wind turbine construction phase than during their operation. Tracking 10 species for 18 UK wind farms before, during and after turbine construction over a three-year period revealed, for the majority of species studied, that numbers were largely unaffected overall. However, two species fell in number whilst turbines were being built and didn’t recover (curlew and snipe), whilst red grouse populations recovered afterwards. The remaining species investigated at the very least recovered in numbers once turbines were constructed, whilst the number of skylarks actually increased overall. Further studies of the impacts of specific species will help assessors review and mitigate potential consequences of wind developments.

Measurement and monitoring is key

Reports typically offer bird fatality figures in terms of the number of birds killed per turbine per year. A study in the journal Energy Policy in 2009 flags the wider risk factors that affect bird fatality rates linked to wind developments, including differing site layouts, turbine technologies used, turbine height, migration routes, bird species density, topography and weather. These may influence bird mortality rates; so extrapolations based on single development assessments without the context may prove misleading. A 2009 assessment of 616 studies on bird death and turbines revealed 80 per cent of these studies only reviewed one or two wind farms.

The use of a standardised mortality rate per unit of electricity, in contrast, enables comparison across electricity sources and provides the broader context in which bird fatalities linked to wind developments should be considered. In a preliminary scoping assessment in the US, compared to other energy sources, bird fatality per GWh was estimated at around 0.27 per GWh for wind, compared to 5.2 GWh for fossil-fuel energy sources. For the US in 2006, that worked out at around 7,000 birds reported killed from wind farms, but many more from nuclear (~ 327,000) or fossil fuel plants (~14.5 million). More recent assessments of the environmental impacts of wind energy conducted in 2011, also note that “the impacts are smaller (for wind) compared to other sources of energy” when it comes to bird fatalities.

How to reduce the effects of wind turbines on birds

Appropriate site selection remains paramount to mitigating the impacts of wind developments on bird populations. A number of practical measures can be implemented to help reduce risks posed to birds.

In 2012, the Journal of Biological Conservation noted in a study of griffon vultures in Spain that death rates were particularly high during the migratory months of October and November. By simply introducing a “selective turbine stopping programme”, death rates were reduced by 50 per cent, whilst the wind farm’s total energy production only fell by 0.07 per cent per year.

Siting developments away from important breeding colonies and establishing alternative nesting sites away from turbines are also useful preventative measures. Technological innovation also has a role to play, as “newer wind turbines…can produce the same amount of electricity with fewer turbines”.

Climate change remains the greater threat to bird species

Alongside the range of peer-reviewed studies that show the mortality rates for birds relating to wind developments as a whole remain relatively low compared to broader human-related causes, wider consideration should be given to the overall threat posed by climate change. The RSPB notes that “climate change poses the single greatest long-term threat to birds and other wildlife, and the RSPB recognises the essential role of renewable energy in addressing this problem”. Indeed, given its readiness as a technology for use, the RSPB are generally supportive of onshore and offshore wind in the UK – where it is appropriately sited.

The threat posed to birds from climate change far outweighs any threat posed by wind developments, which are needed as an essential part of a wider strategy of action to reduce emissions in the UK.

Wind energy is needed as part of the UK’s energy mix to reduce greenhouse gas emissions

Ultimately, the UK needs to act now to decarbonise its power sector and reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Wind energy can be used to displace other fossil-fuel electricity sources as part of this and the UK cannot continue to rely on high-emitting fossil fuels if it is to successfully reduce emissions in line with its targets. As such, renewable, low-carbon sources such as wind have a key role to play as part of the UK’s overall energy mix.

As the Institute’s recent brief notes, “the choice between more affordable electricity (which would favour onshore wind) and local environmental protection (which may favour other low-carbon technologies) is ultimately a political one”. Ultimately, all forms of energy production have environmental impacts, but for wind developments, careful site selection and avoidance of areas of high conservation or habitat value can reduce these impacts on wildlife. On-going monitoring throughout the stages of wind farm scoping and development can help build a greater understanding and detailed picture of possible impacts, and help inform effective planning decisions in the future.

Comprehensive assessments should consider bird migration routes and flight paths, alongside the distribution and densities of rare species, when weighing up planning decisions for wind developments. But ultimately, the UK needs to take action now to decarbonise its electricity sector and reduce its greenhouse gases, and wind energy should play a key role as part of that energy mix.

Read more

To find out more about the basics of wind energy:

- Read our FAQs on onshore wind

- Onshore wind energy UK (policy brief)