Danger of chronic heat exposure for people in developing world’s largest cities

Posted on 6 Sep 2019 in Press releases

In 2018, seven of the largest cities in the world experienced dangerous levels of long-term heat, including Delhi, Lahore and Manila

People in seven of the world’s largest cities are being exposed to dangerous levels of long-term summer heat throughout the day and night, new analysis from the Grantham Research Institute at the London School of Economics finds.

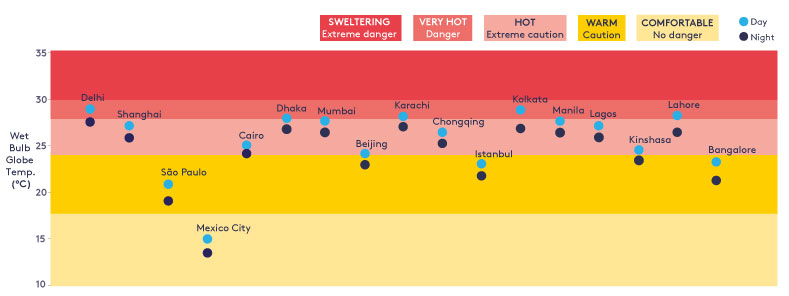

The analysis of 17 of the world’s 20 largest urban areas that are in emerging and developing economy countries finds that in 2018, average summer temperatures in Delhi, Kolkata and Mumbai in India, Dhaka in Bangladesh, Karachi and Lahore in Pakistan, and Manila in the Philippines, reached the threshold beyond which it can be dangerous to undertake physical activity. In total, 123 million people living in the cities were exposed to average summer temperatures at or above this threshold.

A further six cities – Shanghai, Beijing and Chongqing in China, Cairo in Egypt, Lagos in Nigeria, and Manila in the Philippines – experienced average temperatures in summer 2018 that require “extreme caution”, according to the same index, the Wet Bulb Global Temperature (WBGT). This index is most commonly used in workplace assessments and takes account of the four environmental factors that contribute to heat stress: air temperature, relative humidity, wind speed, and radiation (usually sunlight).

To measure the heat stress, researchers calculated the WBGT for people in the 17 cities during day and night time, during the three summer months of 2018. A WBGT of 30 degrees Celsius, which is equivalent to – for example – an air temperature of 40 degrees Celsius and a humidity of 30% in the shade, is the threshold beyond which it is considered dangerous to undertake physical activity.

Most previous research has assessed the dangers of acute exposure to high temperatures, but relatively little is known about the impacts on humans of long-term exposure to chronic heat. It is thought to increase the risks of some illnesses, such as kidney disease, and is also associated with lower productivity in the workplace.

Previous research has projected that as a result of climate change, between 2060 and 2080, most developing countries, including India, central Africa, southeast Asia, and Central and South America, will experience between 50 and 150 days a year that are so hot they are dangerous to human health. This means that for people living and working in these cities, dangerous temperatures are set to become a regular occurrence. The most recent four years of global temperature records – 2015 to 2018 – were the top four warmest years recorded, with 2018 the coolest of the four.

“People in many of the largest cities of the world are already living and working in dangerous conditions of chronic heat exposure each summer,” said co-author Dr Christian Siderius, a research fellow at the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment. “Climate change is set to extend the number of days a year that people are at risk from higher temperatures while going about their daily lives, with serious implications for their health and livelihoods.”

For people living in several cities, night-time brings little relief, as the analysis found that temperatures remained in the “extreme caution” range at night in 11 of the cities, including Delhi, Beijing, Cairo, and Manila, affecting 210 million people. The paper notes that the impact of heat on people’s health is made worse when high temperatures remain at night, as this disrupts sleep and exacerbates pre-existing conditions.

In many of the cities analysed, particularly those in South Asia, temperatures generally start rising in early March, and remain high until the onset of the monsoon in June or early July, after which high humidity adds to the stress on the human body. It is often only in early October that the risk of heat stress significantly reduces.

Previous research has also found that some features of neighbourhoods, including the relative wealth of residents and availability of shade, affect the stress that heat puts on people living in cities. In Delhi (India), Dhaka (Bangladesh) and Faisalabad (Pakistan), high levels of heat stress risk were found in each city on nearly all days that measurements were taken, but denser neighbourhoods were found to be warmer for longer than neighbourhoods that were more open, especially at night. This meant that neighbourhoods where residents generally had higher incomes were more likely to have conditions, including better building design and materials, availability of air conditioning, and shading from trees or buildings at street level, that reduced the risks from heat.

“Not only are the populations of these cities more likely to experience dangerous levels of heat, but it is the poorest and most vulnerable in these cities who are most exposed to the effects,” Dr Siderius said. “To manage the risks from heat in cities governments need to take action on climate, infrastructure and inequality.”

Patrick Curran, policy analyst and co-author of the paper, said: “The largest cities in the world are expanding rapidly and over the coming decades, the risks from heat in these cities will affect hundreds of millions more people.

“Governments and businesses need to take action to preserve the health and productivity of people living and working in these cities sooner rather than later,” he added. “National and city governments need to develop minimum standards that protect the most vulnerable people, and ensure new housing is built in ways that best allow residents to keep cool. Similarly, urban investment plans need to include infrastructure that helps to keep people cool during the day, such as green spaces and shade. Financial institutions such as the World Bank also have a role to play in promoting the recognition of and mitigation against chronic heat issues in construction and infrastructure projects.”

For more information about this media release please contact Kieran Lowe on +44 (0) 20 7107 5442 or k.lowe@lse.ac.uk or Bob Ward on +44 (0) 7811 320346 or r.e.ward@lse.ac.uk.

NOTES FOR EDITORS

- Countries with “Emerging and developing economies” were identified as defined by the International Monetary Fund in October 2018.

- The ESRC Centre for Climate Change Economics and Policy (http://www.cccep.ac.uk/) is hosted by the University of Leeds and the London School of Economics and Political Science. It is funded by the UK Economic and Social Research Council (http://www.esrc.ac.uk/). The Centre’s mission is to advance public and private action on climate change through rigorous, innovative research.

- The Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment (http://www.lse.ac.uk/grantham) was launched at the London School of Economics and Political Science in October 2008. It is funded by The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment (http://www.granthamfoundation.org/).

-ENDS-