Cities, climate change and chronic heat exposure

Headline issues

- Chronic heat exposure can seriously affect health and productivity; climate change will amplify the duration and magnitude of exposure.

- Developing countries are especially vulnerable to sustained high temperatures, due to their location, urban design and poverty levels.

- Decisions on infrastructure investment in urban areas are central to managing chronic heat exposure and to avoiding it in the future.

Summary points

Exposure to high temperatures over long periods can have serious implications for human health, productivity and infrastructure. Many of these impacts are already being felt. Under countries’ current commitments to climate change action, the world is set for 3–4ºC of warming, which could mean an increase in prolonged exposure to extreme heat and exacerbation of these impacts.

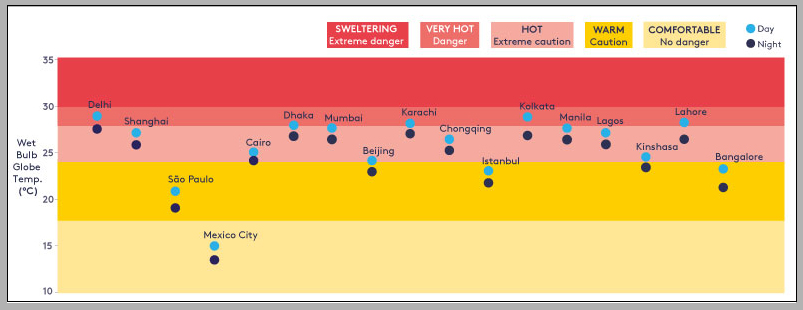

Developing and emerging economies are particularly vulnerable because most are located partially or entirely in tropical regions, and because they are urbanising. Developing countries are home to 17 of the 20 largest cities in the world and Figure 1 shows the levels of heat exposure experienced by these cities across the three summer months of 2018. Urban areas face additional risks from heat because their density amplifies temperatures through the urban heat island effect (see Figure 2 for Delhi illustration), and because of the conditions in and the design of unplanned ‘informal’ settlements, which create conditions that exacerbate heat risks while their residents lack the financial means to mitigate the impacts. The risks are especially high for the elderly, children and the infirm.

Figure 1. Levels of heat exposure in the largest cities in developing countries in 2018

Notes and data sources: Represents average Wet Bulb Globe Temperature (WBGT) during day and night time during the three summer months of 2018, calculated by the authors using data using World Meteorological Organization (WMO) station data and the WBGT calculator from Climate CHIP. WBGT is calculated assuming indoor conditions or in shaded areas; it therefore assumes no direct sunlight and limited wind speed (Lemke and Kjelstrom, 2012). Heat stress levels and categories are based on Blazejczyk et al. (2012). The data in Figure 1 are collected from meteorological stations, which by regulation should be surrounded by open green space thereby shielding them from any urban heat island effect on measurements. 2018 was the fourth warmest year on record (see WMO, 2019).

Figure 2. Increased vulnerability and exposure to chronic heat: example of demographic and urban changes in Delhi, India, 1981–2019

Notes and data sources: The urban heat island effect was estimated by the authors based on the population and rural–urban temperature difference from Oke (1973) for illustration purposes. Delhi has changed not only in size but also in shape over time: these effects were not taken into account in this estimation. In 2011 87 per cent of Delhi’s population did not have access to air conditioning (Desai et al., 2015), largely due to affordability issues. Population figures from Census of India (1981 and 2011); informal settlement data from Chakrabarti (2001) and Census of India (2011); anthropogenic contribution to surface temperature change from Ross et al. (2018). Image by Georgina Kyriacou.

The ability to avoid, manage and build resilience to chronic heat exposure in the future will depend on decisions taken now. Urban design and infrastructure investment, socioeconomic inequality and climate change risks have to be managed simultaneously. Necessary actions include reforming building standards, undertaking vulnerability reviews, and investing in infrastructure that is built to withstand, as well as minimise, chronic heat exposure, particularly in informal, vulnerable areas.

Policy recommendations – summary

To prepare for and manage chronic heat exposure, we recommend a number of actions for different stakeholders, including:

National and regional governments

- Update development policies to reflect the risks of chronic heat exposure to health, infrastructure and productivity. Integrate heat management solutions into resource allocation and activities of all departments.

- Reform housing and building standards to mandate passive heat management techniques (e.g. green roofs) for new buildings. Combine technological heat management solutions with mandatory energy efficiency standards and corresponding investment in renewable energy.

- Introduce support programmes for existing buildings to incorporate heat management technologies, including insulation, roofing and natural ventilation.

Local governments and utilities

- Set minimum requirements for housing developments to incorporate city- and neighbourhood-wide heat management techniques.

- Undertake a vulnerability review of current public infrastructure, both physical (energy, water, transport and housing) and social (health).

- Invest in the appropriate grey infrastructure (e.g. public transport, flexible energy grids, water distribution) and green infrastructure (e.g. permeable pavements, wetlands, water bodies) to address the needs of informal, vulnerable areas.

- Collaborate with representatives of informal areas to identify appropriate and low-cost heat management solutions and raise awareness and disseminate information on chronic heat management options.

Property developers and investors

- Property developers must integrate climate change scenarios and thermal heat indices into project evaluation and design processes.

- Public and private finance investment institutions should undertake a risk assessment of existing portfolios of infrastructure to climate change impacts to reflect risks to operations, returns and users.

Development support and finance organisations

- Develop and fund support programmes in partnership with local governments to identify, develop and implement management techniques for chronic heat exposure, and protect natural areas within urban boundaries.

- Work with community-based organisations to develop support programmes.

- Create specific research grants and programmes that focus on the link between chronic heat related to climate change and urban development in developing countries.